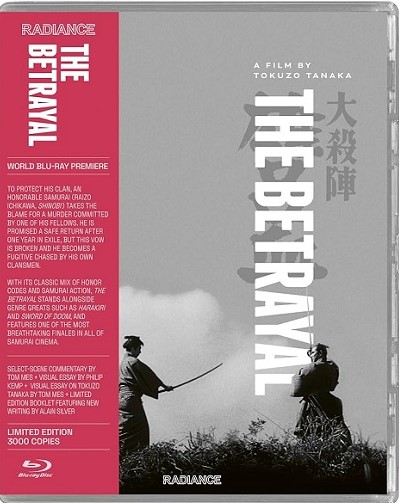

This “Limited Edition” Blu-ray from Radiance Films is now available for purchase.

One of the benefits of time is that a late filmmaker, whose works were once dismissed, can actually be reevaluated and find a new life and audience. Such is the case with Tokuzô Tanaka, a Japanese artisan who got his stars as assistant director on classics like Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950) and Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu (1953). After paying his dues on other people’s projects, Tanaka branched out on his own as director, making several notable B-pictures including Zatoichi’s Revenge, The Snow Woman, Shinobi 4: Siege, and The Haunted Castle (to name but a few). They were mostly successful, but didn’t gain much critical attention and disappeared after their original releases. However, in recent years that has all changed. Now, several of his pictures are being rereleased on Blu-ray and given new attention from film authorities.

The Betrayal is certainly one of Tanaka’s efforts that continues to grow in esteem as the years pass. It’s a unique samurai film that doesn’t follow tradition, presenting the warrior’s world as less-than-honorable and delivering a stunning finale quite unlike other pictures of its ilk. Radiance Films has now acquired the release rights to the feature in the western world. The high-definition digital transfer of the movie from the Kadokawa Corporation is remarkably strong, delivering a sharp, clean image for the black and white feature that manages to highlight the underrated cinematography.

The story sees a good, well-intentioned samurai Takuma Kobuse (Raizo Ichikawa) about to be married. All he wants is to serve his duties in an honorable manner. But when the son of an elder in his faction murders an important member of another samurai group, Kobuse is asked to take the blame. He is told this will only be for a short time, requiring one year of exile before the details of the situation are revealed, his honor is restored, and he can move forward with his nuptials. Sadly, this is not what occurs. As a lower-class member of his warrior group, those above him are more than happy for the problem to completely go away. That means that Kobuse will officially take the blame and be eliminated. His own master and family members, including the murderer all seek to eliminate him, as do the relatives of the slain figure, bounty hunters, and others enforcing the law.

If that wasn’t bad enough, while living on his own as a ronin, Kobuse learns that those he assists on his travels are more than willing to take advantage of him. A man who joins him on his journey (who in these types of pictures would normally serve as an assistant and provide comic banter) ultimately sells the hero out for a few coins. And Kobuse’s fiancé ends up having to support herself during his absence providing services for nasty figures. Completely disillusioned with the hypocrisy of the samurai world, the protagonist eventually finds himself squaring off against all those who want him dead in a final and lengthy showdown. By this point, many men, including the family of the man originally killed, know that Kobuse is innocent. Yet they feel compelled to follow through and murder him for tradition and the sale of appearances.

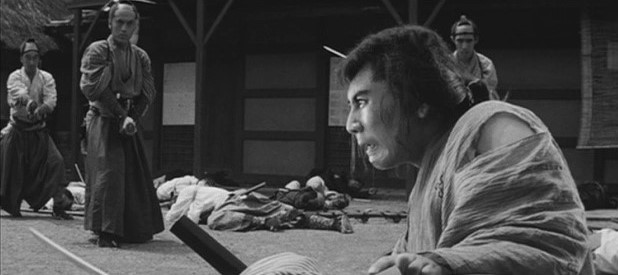

This unique spin on the samurai film really helps the picture stand out. Ichikawa is a charismatic lead and one really feels for him as seemingly everyone, both metaphorically and occasionally literally, tries to stab him in the back. And the final act, which involves over two-hundred fighters from various factions arriving on his doorstep, leads to a memorably wild 15-minute confrontation. While certainly stylized and not exactly realistic, this finale is remarkable and entertaining to watch as body after body falls to the ground. It is also notable for presenting its massive battle as hard fought for the protagonist, as the increasingly exhausted Kobuse mows down everyone in his path.

It’s certainly a familiar type of warrior story, but the actions of those around the lead character and the criticism it delivers at the feet of this famous warrior class makes a strong impression. This film definitely sticks with the viewer long after the credits roll, and it’s great to see it getting the attention it deserves.

As mentioned, the image quality is very good with dark blacks and remarkable detail visible (the stills used in this review don’t do the film justice). Again, for what must have been a B-movie, it looks impressive and that epic climax, while over-the-top, is as crisp, dynamic and exciting to watch as any A-list samurai effort.

The extras are also illuminating. There is a scene-specific commentary with Asian cinema expert Tom Mes, who goes over many of the unique elements of the film. He discusses the themes presented in more detail, explaining some of the traditions and how those of higher social standing could and would manipulate others to prevent themselves from falling under the knife. He reveals that the world presented is unusually harsh and it’s a great track.

This film is also not an original project, but a reimagining of a 1925 silent Japanese picture called The Serpent. A visual essay shows clips of the original feature and goes into the differences between each version. There is a lot of trivia given about both projects. It seems that telling a story about an outlaw ronin was something that would have been frowned upon in the 1920s, which resulted in the early version’s unusual title. The essay also shows all the negative aspects of the samurai and gets into more detail about the elaborate finale in the 1966 version. The speaker notes that despite the fact that Kobuse does end up surviving the fracas, the close feels awfully bleak. I think that is certainly true given all the bloodshed, but the nature of the tale makes it hard to imagine the leads laying down and dying as being any less grim. In any telling regardless of the end result, it would be a dark and heavy story. This essay presents some great insight and thoughts on the picture and its effectiveness.

Additionally, Tom Mes presents another visual essay going into key themes or motifs in the director’s work. Natural elements like fog, mist, dirt and fire are frequently being thrust into the frame and you’ll see specific examples. And the critic notes some of the framing and editing techniques used in the films, noting that during the fight scenes, traditional wide angles and long takes are used (but, in The Betrayal, the fights are broken up with very quick close-up inserts of blades and implements crashing together that liven up the proceedings). Sadly, no one interviewed Tanaka during his lifetime to get more insight into his preferred storytelling techniques and why he used them, but it’s exciting to hear an expert on the subject give his opinion.

And the disc contains a booklet with a written essay that contains more arguments about ideas in the film that may not immediately spring to mind upon first viewing.

There are plenty of samurai pictures out there, but The Betrayal is a notable effort that does make a lasting impression. It’s a powerful movie and one that was certainly underrated during its original release. This “Limited Edition” Blu-ray will certainly help to build its fanbase, delivering a great picture and some enlightening bonuses. If you enjoy classic Japanese cinema, it’s deserving of your attention and definitely worth picking up.